Extracted/ English version Summer 2024- Ecology: Gone with the (Geopolitical) Wind ?

International readers : this post is for you. French-speaking subscribers, we advise that you switch to this section: https://exfiltrees.substack.com/

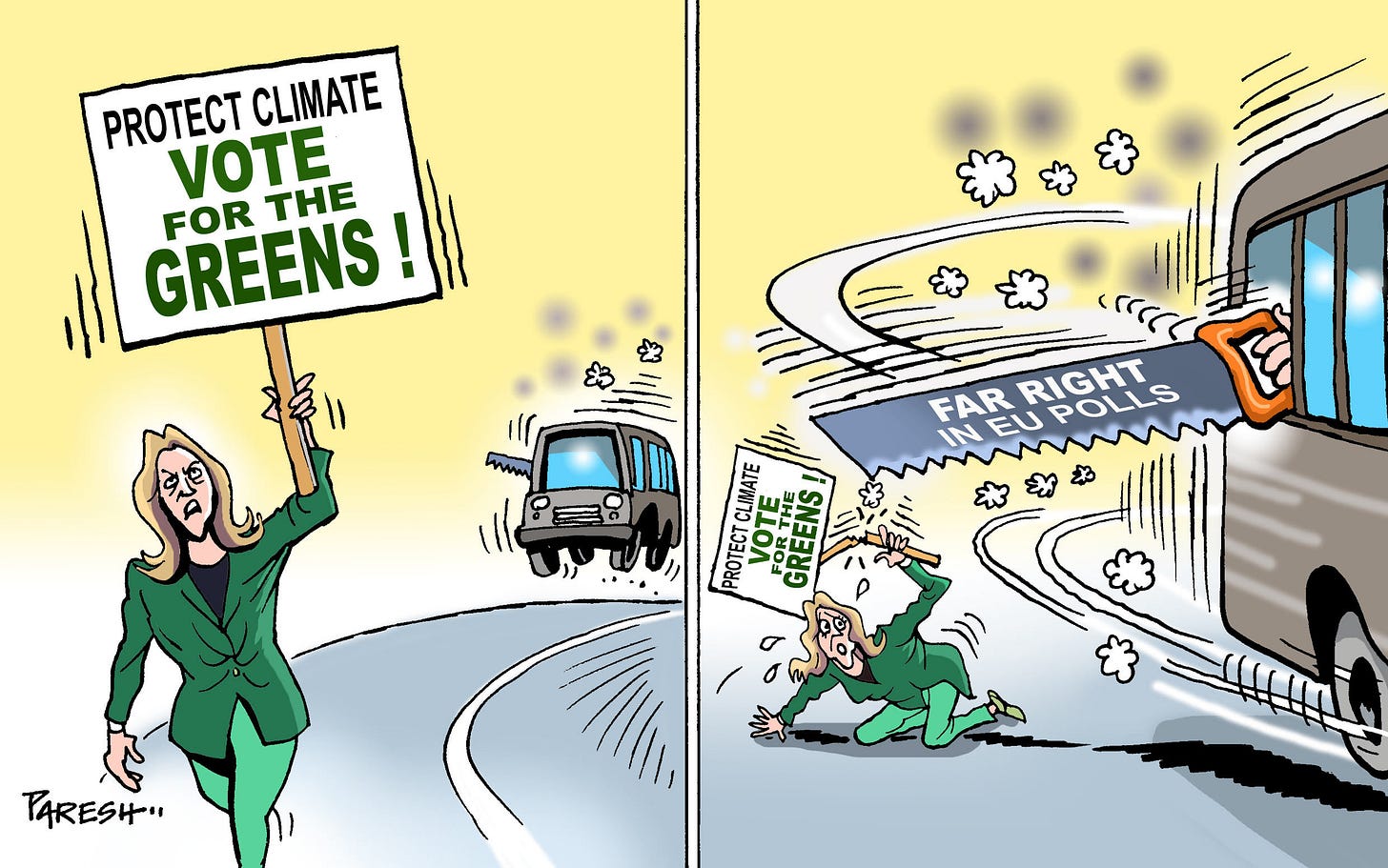

A recent survey by the Foundation for Political Innovation, recording the opinions of over 23,000 European citizens ahead of the elections, is unequivocal. Aside from the Ukraine conflict, the main concerns of Europeans are financial and social inequalities on the one hand, and illegal immigration on the other. While these two issues appear to define the political landscape today, concerns about climate change slip to the sixth position, and the share of green MPs at the European and national levels is declining. In the United States, a Trump victory would put climate issues back at the bottom of the priority list.

Could this lack of interest in the ecological question be discouraging? A systemic view leads us to believe that the environment must, more than ever, be at the center of our thinking. The ecological shift has long-term implications for the economic, social, and geopolitical issues that concern citizens. These are the thoughts that fuel the theme of this summer's issue.

We hope you’ll enjoy reading, and many thanks to our new subscribers! Feel free to share your comments, remarks, and suggestions.

End of the world versus end of the month

For many, ecology and the energy transition are distant concerns: an “urban ideology”, as the French far-right party likes to call it. Issues that do not concern those struggling to make ends meet. Yet it is the exploitation of fossil fuels that has enabled a significant rise in global GDP since the Industrial Revolution. Conversely, as access to these resources dries up, many observers anticipate an inevitable economic contraction.1 Thus, rather than pitting ecological considerations against people's financial concerns, we need to bring these issues and the public policies associated with them closer together. An orderly (rather than unplanned) energy transition would limit the economic impact of finite energy resources (and, more broadly, of natural capital).

Economic shocks and inequalities are likely to multiply as climate catastrophes increase

Heat waves, ocean acidification (and rising sea levels), declining agricultural yields linked to climate hazards and soil exhaustion... All these changes are threatening growth by contributing to population displacement, social unrest and the drastic depreciation of certain assets. According to the Banque de France, the scenarios of a “disorganized” transition (without planning) lead to impacts of -2.1% and -5.5% on French GDP by 2050. It would also lead to greater inequalities, both nationally and globally. This can already be seen in the rise in energy bills, the proportional weight of which is greater for poorer households. These costs could be perceived as all the more unfair given that it is the wealthiest countries and individuals who contribute the most to climate disruption, not least through their leisure activities.

The top 10% CO2 emitters are responsible for 50% of emissions

Based on this observation, it is easy to anticipate how increasing economic shocks and inequalities will contribute to an unstable world in which populism could flourish, making people believe that challenging the established order alone will solve problems, thereby diverting attention from the underlying physical problems and the structural changes that should follow.

The report also highlights the fact that purchasing power and economic growth cannot be the only relevant indicators for measuring people's well-being and structural inequalities in access to quality of life, health, care and education.

How can we plan ahead?

Given the connection between climate change, economic hardship and growing inequality, it is essential to link public transition policies to their effects on present and future inequality. As the yellow vests crisis2 has demonstrated, the ecological transition will only succeed if it is perceived by the majority as fair to deploy necessary efforts and investments.3 A simple “tax” is not enough, as it implies that the stakeholders most responsible for the climate problem continue to access the same services by paying more, while the poorest no longer have access to them.

In 2023, at Elisabeth Borne (French Prime Minister) 's request, Jean Pisani-Ferry and Selma Mahfouz, former Commissioner General and Inspector General of Finance respectively, published a very detailed report on these issues in 2023. (The economic implications of climate action).

Some key points:

From the outset, the report lays the groundwork: “Climate neutrality will not be achieved through economic decline. It is certainly by mobilizing the margins of sobriety, but above all by decarbonizing energy through the substitution of capital for fossil fuels and by redirecting technical progress towards green technologies”.

To achieve this (and to meet France's climate objectives), colossal investments would be required: France would have to deploy 100 billion of investment by 2030.

Most of these investments would be very difficult for less well-off households to bear. For example, according to the report, renovating a home, changing the heating system and acquiring an electric vehicle to replace a combustion-powered car represents an investment representing around one year's income for the average household in France.

Thus, even an approach that prioritizes economic equilibrium over radical climate action finds that strong redistribution and effort-sharing actions are needed. The report examines several financing options:4

The end of “brown” tax expenditures, essentially fuel tax exemptions for certain professions. Exempting aircraft from kerosene tax represents a loss of 34.2 billion euros in tax revenue per year in Europe, according to some estimations.

Debt: to bet everything on this aspect would be ‘imprudent’, concedes the report, which points out that convincing the rating agencies of this approach is a challenge worth exploring.

Temporary taxation of the highest incomes: mandatory and exceptional levies applied to the wealthiest households to “show that everyone is contributing to the effort”.

Such investment will have a positive mid-term effect on growth by boosting demand. But because it will be geared towards reducing fossil fuels rather than expanding production capacity, the transition will mean a temporary slowdown in the productivity of new labor market needs.

This leads us to explore the other side of the spectrum of concerns highlighted by polls.

What About Immigration?

As highlighted by François Gemenne, a Belgian political scientist specializing in climate and environmental migrations and a member of the IPCC5, migrations are currently approached by the political world from an ideological and "poll-driven" perspective, without anticipation or forward-looking vision, and without any real consideration of climate migration phenomena.

Certainly, current migrations seem primarily linked to economic and geopolitical issues rather than natural disasters. However, climate change already plays a major role in these two factors, and this will only intensify: a large part of the income and livelihood of the least developed countries directly depends on climatic conditions through agriculture, as is the case for 70% of the inhabitants of the Sahel.

According to François Gemenne, the road to hell is paved with good intentions: the idea of massive flows of climate migrants towards Europe was presented to encourage developed countries to act to reduce their emissions, but in doing so, it reinforced the negative vision of these flows, presented as a threat, thus fueling the rhetoric of the far right and the logic of absolute border closure6. This policy has been completely ineffective in deterring aspiring migrants and encourages those who manage to cross the border to never leave, as the journey is costly and dangerous.

The reality is more complex. Not only are climate migrations, intertwined with economic and political factors, already a reality, but most displacements occur within countries or to neighbouring countries, rather than to developed countries (more than 200 million internal displacements by 2050 according to the World Bank). There will also be increasing intra-European migrations, particularly due to droughts in Southern Europe or submersions in coastal areas.

Regarding the scale of asylum seekers to Europe, projections are very difficult to make due to the intertwining factors of migration. However, statistical work conducted jointly in 2017 by researchers from Columbia University based on previous deviations from optimal temperatures provides the following projections: a 28% increase in asylum seekers per year in Europe for a 2.2-degree warming (98,000 additional requests), and a 188% increase for a 3.9-degree warming (660,000 additional requests per year).

To best manage the climate transition and mitigate the consequences of changes already underway, there will also be a great need for skilled labour, particularly in the fields of construction and agriculture. More broadly, maintaining a good proportion of active workers in ageing European populations will not be possible without welcoming new people. In Europe, the total loss of the active population between 2021 and 20507 would be 40 million if immigration does not increase, which is more than one million fewer active workers per year. Thus, a preventive and reasoned migration policy is an integral part of the adaptation strategy within the framework of ecological planning.

Finally, as we recalled in our article on the COPs, developed countries have consumed a large part of humanity's carbon budget, and recognizing this responsibility towards the most vulnerable populations of the Global South should encourage us to show more empathy, or at least a willingness to cooperate. A more collaborative and less defensive international approach to migration issues, as well as climate issues, is key to better studying, anticipating, and organising rather than enduring.

Reflecting and acting together, in a fair and reasoned manner, on our common future—isn't that the essence of politics?

Did you enjoy this newsletter? Feel free to subscribe to receive the next issues!

(On this subject, see the Shift Project's studies on the depletion of oil and gas resources).

To be compared with other waves of protest in Europe, for example in Sweden, the “fuel revolt” was exploited by the far right.

In this respect, we need to distinguish the question of justice from that of social acceptability: certain tax measures may be considered fair in theory, but meet with strong resistance in public opinion. For example, a carbon tax whose revenues would be earmarked for adaptation to global warming in developing countries, or to finance “loss and damage” for future generations, may be considered morally just, but would prove very difficult to gain acceptance for.

The report focuses primarily on the climate issue and does not take into account other criteria, such as biodiversity.

François Gemenne heads the Hugo Observatory dedicated to environmental migrations.

It's worth noting that the former director of Frontex from 2015 to 2022, who resigned notably due to serious accusations of complicity in crimes against humanity, has joined the National Rally (RN) list in third position for the 2024 European elections.

https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/6453758?sommaire=6453776#titre-bloc-1